Cirrhosis of the liver occurs when healthy liver cells are replaced with scar tissue and correlate with gastric varices by about 50 percent. When it is left untreated, portal hypertension will cause gastric varices in approximately 20 percent of patients. In cases when cirrhosis of the liver is not present, gastric varices are most often the result of splenic vein thrombosis, a complication of acute pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer, or other abdominal tumors.

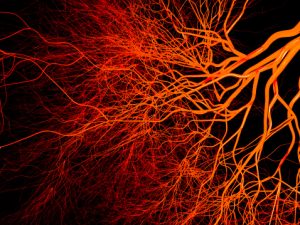

The submucosal veins in the stomach become dilated, which are called gastric varices. If the veins burst, they can cause internal bleeding. Depending on the severity, they can be life-threatening. Other symptoms include hemoptysis (coughing up blood), black tarry stools, or rectal bleeding.

Classification of gastric varices

There are three major classifications of gastric varices, as follows.

Sarin’s classification is defined by the location of the gastric varices in the stomach and their relation to esophageal varices. Sarin’s is the most used classification system. It is then further sub-classified under four distinct types of gastric varices: Gastroesophageal varix (GOV) type 1, Gastroesophageal varix (GOV) type 2, Isolated gastric varix (IGV) type 1, and Isolated gastric varix type 2. Both GOV types of gastric varices under Sarin’s classification are viewed as extensions of esophageal varices and are treated very similarly. GOV type 1 accounts for 74 percent of all incidents of gastric varices. IGV type 1 and GOV type 2 are the two most common types associated with bleeding of the varices. In terms of predicting hemorrhages, size is the largest factor.

The hashizome classification includes three different types of gastric varices. They are characterized by form, location, and color of the varices. Based on their shapes, varices are described as either Tortuous, Nodular, or Tumorous. Locations are broken down into anterior (front), posterior (back), lesser curvature (the shorter length of stomach between the esophagus and the duodenum), greater curvature (the longer length of stomach between the esophagus and the duodenum), and fundic (upper part of the stomach). Varices are either red or white, with red color varices being at a higher risk of bleeding.

Arakawa’s classification separates gastric varices into only two types. When the varices are formed by only one supplying vessel, they are type 1a. When they are formed by two or more supplying vessels, they are type 1b. Type 2 is characterized by the addition of other stomach wall vessels to the varices, apart from the main supplying vessels.

What are the causes and symptoms of gastric varices?

Gastric varices are primarily caused by portal hypertension. With the increased pressure in the portal veins, blood is pushed away from the liver and into smaller blood vessels that are ill-equipped to handle the excess amount of blood being transferred into them. This causes the smaller veins to become swollen, otherwise known as varices. When formed in the stomach area, these are called gastric varices. As the veins are swollen, the vein walls are much thinner and more susceptible to rupturing than normal.

If they remain unbroken, gastric varices show no symptoms. Once they start to bleed, varices can result in any number of the following symptoms. Coughing up blood or blood-stained mucus, vomiting blood, black and tarry stool, blood in the stool, hypotension (low blood pressure), tachycardia (increased heart rate), light-headedness or dizziness, and in some cases the patient may go into shock. Bleeding gastric varices are considered a medical emergency and should be treated immediately. If not treated, the patient can suffer extreme blood loss and even death.

How to diagnose and treat gastric varices

Diagnosing gastric varices often requires an endoscopy for confirmation. An endoscopy is an imaging procedure, similar to an ultrasound, that allows a doctor to view the inside of your digestive tract. Other types of imaging technology used to diagnose gastric varices include computed tomography scan (with contrast), transabdominal ultrasound with Doppler, interventional angiography, magnetic resonance angiography, and portovenography.

Treatment for gastric varices that are bleeding focuses on stopping the bleeding. Blood transfusions are often needed to replace the blood being lost from the bleeding varices. Endoscopic variceal ligation is the most common technique used when treating gastric varices. It involves placing a band, much like a rubber band, around a section of the bleeding vein to cut off blood flow to the site of bleeding. Sclerotherapy is also a treatment option, where certain medicines are injected directly into the veins, causing them to shrink. Alternatively, endoscopic injections can be used to place tissue adhesives at the site of bleeding, forcing the tissues to clot and control the bleeding. This is most often done with thrombin, which is a clotting agent.

Gastric varices are caused by portal hypertension, generally due to underlying liver issues. They are found in 50 percent of liver cirrhosis patients. Portal hypertension forces blood from the portal veins into smaller blood vessels in the stomach area that are unable to handle the additional amounts of blood, causing them to swell and sometimes burst.

Before they rupture, gastric varices are asymptomatic. If the varices burst, the internal bleeding they cause can become life-threatening. The internal bleeding from gastric varices causes patients to cough up blood, vomit blood, have bloody or black and tarry stools, and eventually dizziness and shock. Diagnosis of the condition requires internal imaging technologies, most often endoscopy. Treatment focuses on stopping the internal bleeding and can vary between physical blockage of the vein and clotting enhancements.

Related: Cirrhosis of the liver: Life expectancy and stages