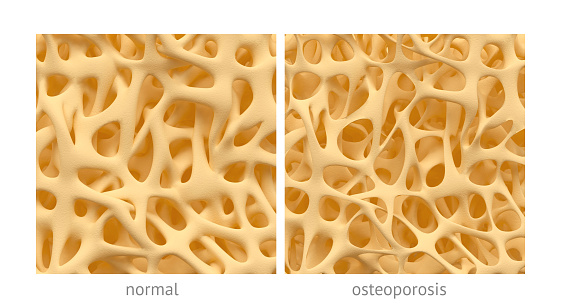

Osteoporosis affects nearly 200 million individuals worldwide, most of them women, although the risk of osteoporosis is equal for both sexes. In osteoporosis, the inner structures of the bones begin to diminish, making the bones thin, less dense, and lose their function. Osteoporosis increases the risk of fractures, with hip fractures being the most common injury in osteoporosis.

Senior author of the study William Stanford said, “We reasoned that if defective MSCs [mesenchymal stem cells] are responsible for osteoporosis, transplantation of healthy MSCs should be able to prevent or treat osteoporosis.”

The researchers injected osteoporotic mice with MSCs from healthy mice. MSCs are able to become bone cells and they can be transplanted from person to person without matching – unlike in blood transfusions, for example.

After six months of the injection, the osteoporotic bone had become healthy and functional.

Coauthor of the study John E. Davis added, “We had hoped for a general increase in bone health, but the huge surprise was to find that the exquisite inner ‘coral-like’ architecture of the bone structure of the injected animals—which is severely compromised in osteoporosis—was restored to normal.”

The study gives hope that in the future osteoporosis could be postponed or even reversed through stem cell injections. First author Jeff Kiernman said, “We’re currently conducting ancillary trials with a research group in the U.S., where elderly patients have been injected with MSCs to study various outcomes. We’ll be able to look at those blood samples for biological markers of bone growth and bone reabsorption.”

New potential treatment for osteoporosis

Researchers from the Florida campus of The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have uncovered a therapeutic approach that could potentially help develop bone-forming cells in osteoporosis patients. The study focused on a protein known as PPAR and its impact on stem cells derived from bone marrow. These cells can develop into many other cells and can have large implications on many therapeutic applications.

The researchers already knew that a partial loss of PPARy in genetically modified mice could lead to an increase in bone formation. In order to determine if they could replicate these results using a drug, the researchers combined a variety of structural biology approaches to rationally design a new compound that could repress the biological activity of PPARy.

When the human stem cells were treated with a new compound called SR2595 (SR=Scripps Research), there was a statistical increase in formation of osteoblasts, which are known to form bones.

Director of the Translational Research Institute at Scripps Florida Patrick Griffin said, “These findings demonstrate for the first time a new therapeutic application for drugs targeting PPARy, which has been the focus of efforts to develop insulin sensitizers to treat type 2 diabetes. We have already demonstrated SR2595 has suitable properties for testing in mice. The next step is to perform an in-depth analysis of the drug’s efficacy in animal models of bone loss, aging, obesity, and diabetes.”

“Because PPARG is so closely related to several proteins with known roles in disease, we can potentially apply these structural insights to design new compounds for a variety of therapeutic applications. In addition, we now better understand how natural molecules in our bodies regulate metabolic and bone homeostasis, and how unwanted changes can underlie the pathogenesis of a disease,” added first author David P. Marciano.