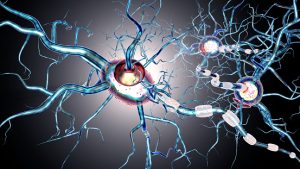

The condition is thought to be the result of the body’s own immune system attacking myelin sheaths – a specialized membrane enriched in lipids (fat) surrounding nerve fibers. Now, a team of researchers from the Technical University of Munich (TUM) has found a possible explanation for this phenomenon.

Multiple sclerosis

The destruction of myelin leads to communication problems between the brain and the rest of the body, causing MS symptoms, with permanent damage to these nerves being an eventuality. Additionally, the body’s ability to regenerate myelin decreases with age.

Autoimmune disorders like MS result from innate immune cells attacking healthy tissue. The myelin covering nerve fibers can be compared to that of the protective coating found on electrical wires. If it were to get damaged, the electricity would not reach its destination. When the protective myelin is damaged and the nerve fiber is exposed, the message that was traveling from the brain along the nerve may be slowed or blocked.

Multiple sclerosis is thought to develop in people due to a combination of genetics and environmental factors. Signs and symptoms of the disease may differ greatly from person to person depending on the location of the affected nerve fibers. What follows are some of these presentations:

- Partial or complete loss of vision – usually in one eye

- Prolonged double vision

- Tremor or lack of coordination

- Numbness or weakness in the limbs on one side

- Tingling or pain in parts of the body

- Fatigue

- Slurred speech

- Dizziness

- Problems with bowel and bladder function

It is not known why immune systems attack myelin, but what is known is that persistent inflammation prevents myelin regeneration, a hallmark finding in multiple sclerosis.

An explanation that could lead to new therapy

Mikael Simons, a molecular neurobiology professor at TUM, provides a possible explanation for this process, describing how fat derived from myelin is not carried away fast enough by phagocytes (cells that protect the body by ingesting harmful foreign particles, bacteria, and dead or dying cells).

“Myelin contains a very high amount of cholesterol, when myelin is destroyed, the cholesterol released has to be removed from the tissue,” says Simons.

In order to maintain adequate functioning of cells, microglia and macrophages (also referred to as phagocytes) consume damaged components to be taken outside the cell so they can be recycled properly. However, this does not occur in multiple sclerosis. Instead, cholesterol builds up, forming needle-shaped crystals, causing damage.

This was demonstrated using mouse models, in which Simons and his team showed how damaging these needle-like cholesterol particles can be. Activation of inflammatory mediators and subsequent inflammation was seen as a result.

“Very similar problems occur in arteriosclerosis, however not in the brain tissue, but in blood vessels,” Simons continued.

The researchers say that age also dictates how well immune cells do their job. As age increases, they are less effective at clearing cholesterol, resulting in stronger chronic inflammation.

The team then treated their animal models with medication that facilitated the transport of cholesterol out of the cells, finding that when inflammation decreased, myelin was regenerated. Their next goal is to investigate whether this can be translated to promote regeneration in patients with multiple sclerosis.

Related: Resistance training shown to improve multiple sclerosis patient outcomes